16 Sep 2021

Amanda Matthes & Jonas Beuchert track sea turtles in Cape Verde to test new conservation technology

Can we locate endangered sea turtles using twelve milliseconds of noisy satellite signals?

Amanda Matthes and Jonas Beuchert (EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Autonomous Intelligent Machines and Systems)

As part of our research with Professor Alex Rogers, we have developed SnapperGPS, a low-cost, low-power wildlife tracking system based on satellite navigation. In summer 2021, we deployed it for the first time on wild animals: endangered loggerhead sea turtles in Cape Verde.

Location tracking devices are an important tool for biologists to study animal behaviour. Usually, they use global navigation satellite systems like the GPS for this. However, existing devices are often expensive and come with heavy batteries for long-term deployments. One tag can easily cost more than $1000, which prohibits studies with many animals. That is why we developed SnapperGPS.

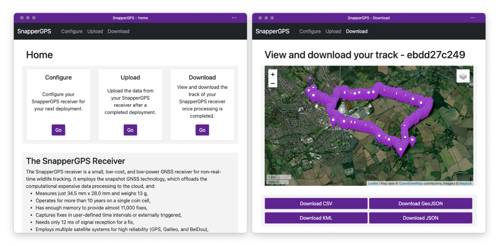

SnapperGPS aims at being a cheap, small, and low-power tracking solution. Its core idea is to make the hardware as simple and as energy efficient as possible by doing as little signal acquisition and processing on the device as possible. Instead, we created a web service that processes the signals in the cloud. This allows us to build a bare-bone receiver for less than $30, which runs for more than ten years on a coin cell.

The concept that we employ is known as snapshot GNSS. Its advantage is that a few milliseconds of signal are enough to locate the receiver. With SnapperGPS we face the particular challenge that the hardware records signals at a much lower resolution than existing receivers. To address this problem, we developed and implemented three alternative algorithmic approaches to location estimation from short low-quality satellite signal snapshots, which are all based on probabilistic models.

In summer 2021 we were able to deploy SnapperGPS on nesting loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) on the island of Maio in Cape Verde. Loggerhead sea turtles spend most of their life in the ocean, but every two to three years mature females come to a beach to nest. They lay several clutches of eggs separated by roughly two weeks, which makes it possible to recover the hardware and any data it captured.

Navigation satellite signals cannot travel through water, but sea turtles regularly come to the surface to breathe. These short windows of opportunity may not always be enough for traditional GPS methods to resolve the position of the receiver. But a snapshot method only requires milliseconds of the signal which makes them ideal for such marine applications.

For this turtle deployment, the SnapperGPS tags were placed into custom-made enclosures that were tested to be waterproof to at least 100 m.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we had to deploy the tags late in the nesting season which negatively affected our recovery rate as many turtles were already laying their last nest when they were tagged. We deployed twenty tags and recovered nine. Some experienced unexpected technical failures but we were able to capture several location tracks that showed unexpectedly diverse behaviour among turtles. This data provides novel insights into the loggerhead sea turtle population on Maio. We also learned about the specific challenges of deploying SnapperGPS on a sea turtle and will work on an improved version for next year’s nesting season.

Wildlife location tracking data can inform conservation policy decisions that help protect habitats and prevent human-wildlife conflicts. In the case of loggerhead sea turtles, understanding their movements can inform where to direct anti-poaching measures and it can identify important marine habitats that may need special protection.

SnapperGPS is supported by an EPSRC IAA Technology Fund. Additionally, Amanda and Jonas receive support from the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Autonomous Intelligent Machines and Systems (AIMS CDT). The field work was made possible through a cooperation with the Maio Biodiversity Foundation and the Arribada Initiative.

Figure 1: A SnapperGPS board next to a £1 coin. It measures 3.5 cm x 2.8 cm.

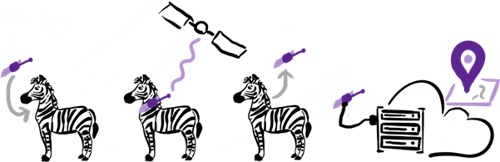

Figure 2: Once configured, SnapperGPS regularly collects snapshots of satellite data. After retrieval of the device, the collected data is uploaded to the cloud where the location track is computed.

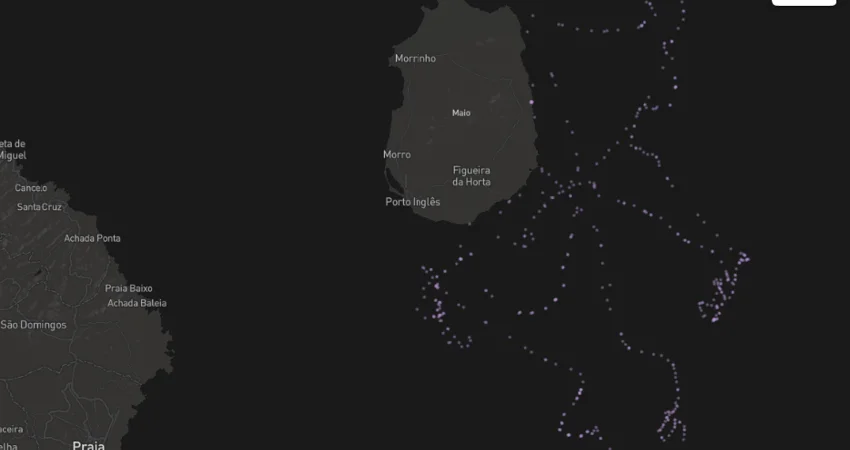

Figure 3: A web application serves as the front end for configuring SnapperGPS devices, uploading data logs and downloading computed location tracks.

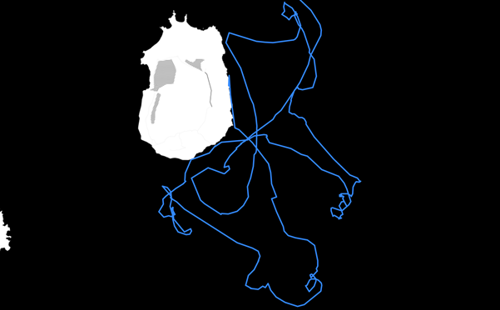

Figure 4: A location track of a loggerhead sea turtle captured by a SnapperGPS tag.